Ghana: The politics of health and the people

According to Patrick Rothfuss “It’s like everyone tells a story about themselves inside their head. Always. All the time. That story makes you what you are. We build ourselves out of that story.”

According to Patrick Rothfuss “It’s like everyone tells a story about themselves inside their head. Always. All the time. That story makes you what you are. We build ourselves out of that story.”

In this last week, I have been reviewing elections in Ghana since 1992 and how the conversations around health have evolved. In all these elections, the electorate has been told stories by our politicians based on the assumption they know what we need to keep us healthy. Often, as citizens we have failed to ask questions and have swallowed information, they provide hook, line, sinker and rod. As a result, post-elections winning parties set out in a half-hearted manner to implement what they promised.

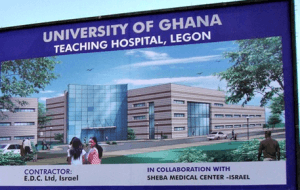

Twenty-six years on, our health indicators have seen only marginal appreciation. Yet both leading political parties, that have had the opportunity to govern this country always point to achievements they have had in the area of health. Often, in the area of physical structures and other procured resources. Why then have indicators like life expectancy and quality-adjusted life-years failed to reflect these perceived achievements?

For me there can be only one reason; the narrative around health we have received for this last quarter of a century is wrong. If this assumption is right then why have we as citizens accepted and believed it? In my view, it is because as a people we don’t really know what we want in terms of healthcare provision and thus are always making the wrong demands for this public service. I will illustrate this further.

Twenty-six years on, our health indicators have seen only marginal appreciation. Yet both leading political parties, that have had the opportunity to govern this country always point to achievements they have had in the area of health.

The Late President Mills then-presidential candidate promised that it was possible to run the National Health Insurance Scheme using the concept of a “One-time premium” payment. When this electoral commitment was made, there were no financial numbers or projections to buttress the claim. As we always do, the debate then became dominated by politics and not critical scrutiny of the policy’s feasibility. Following electoral victory in 2008, it did not take long for the Mills government to eat humble pie and accept that what had played a huge part in bringing electoral success was a fluke. As citizens, we turned a blind eye and waited patiently for the next story or next elections.

Another example can be seen in the restoration of nurses’ allowances which dominated the 2016 election campaign. At the time of that debate, the Mahama government had gone to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) under the guise of obtaining financial credibility. As a result, there was a cap on public service recruitment with a backlog of nurses to be employed. Yet the debate was not had based on the prudence or otherwise of restoring the allowance when the camp of then-candidate Akufo-Addo  announced it. Instead, we once again went on a political emotional roller-coaster. In the end, following the 2016 NPP victory, the allowance was restored. Leading to a situation where we are giving monies to student nurses, we know the public sector cannot readily employ. I leave the reader to judge the prudence or otherwise of such a move.

announced it. Instead, we once again went on a political emotional roller-coaster. In the end, following the 2016 NPP victory, the allowance was restored. Leading to a situation where we are giving monies to student nurses, we know the public sector cannot readily employ. I leave the reader to judge the prudence or otherwise of such a move.

A simple look at most of our public health facilities would show that many have buses. I have occasioned to ask a colleague of mine who is a medical director how these buses contribute to effective healthcare delivery? The irony also is that many of these facilities do not have functional ambulances for patient transfer or if they do, basic lifesaving resources are not available. Yet, the system has conspired to see it fit those vehicles that mass transport staff to social functions such as funerals and weddings are the priority and are constantly requested for when politicians visit these facilities. Truth is, these are a drain as limited financial resources are spent on maintenance, fuel, wear and tear.

I foresee the narrative around health being based on Mahama’s infrastructure drive versus Akufo-Addo’s promise of ambulances and vehicles for the health sector.

With next year fast approaching, our votes are going to be sought again and with its promises around health. It is also an election where a former president’s record is going to be pitched against that of the sitting president. I foresee the narrative around health being based on Mahama’s infrastructure drive versus Akufo-Addo’s promise of ambulances and vehicles for the health sector. I anticipate that the NDC would be questioning why hospitals built under their stewardship have not been operationalised by the current government. I also see the NPP rebutting and pointing to the ambulances and pickup trucks that would by then be visible on our streets.

As electorate who believe in cosmetics and tangibles, we would go into emotional arguments shouting ourselves hoarse trying to quantify which of the two political colours is worthy of or thumbs. Whilst at it we would fail to grill these politicians on how any of these interventions they tout have improved healthcare delivery and our collective quality of life. We would also fail to question for example the rationale of putting up more health facilities without a clear blueprint on how they were going to be kitted by way of human resources based on our precarious health professional to population ration. We

would also fail to drill down and ask for example how with 2,551 health facilities requiring doctors and a total doctor population of 4016 (facility to doctor ratio 1: 1.57) we still feel that the solution lies in buildings and edifices. We would engage in a political tag of war forgetting that all these facilities have come at a considerable sunk cost and would not question the current government on its strategy to remedy the situation.

We will also fail to question how the Finance Minister in one breath will say he wants to drop the wage component of total healthcare expenditure to under 50 per cent from its current 61 per cent, yet, the Health Minister will be promising a recruitment drive for health professionals in 2020. So, would we ignore the fact that most of the pickups purchased for district health offices would not impact on health delivery and outcomes significantly but would most likely be commandeered by district directors for their personal and family convenience.

My view is that in 2020 we should refuse to allow the politicians to set the health agenda but be clear in our minds what we want by way of health delivery and the efficiencies thereof. We should be well-armed with our current health numbers and how they have trended under both political parties. We must then ask the relevant questions based on their respective previous performances and how they are going to bridge the gap with what our expectations are.

To do this will require us to first understand the basics of what goes into healthcare funding, what the main drivers of health improvement consist of and why our politicians never focus on these. We must understand that health improvement cannot be procurement driven but must be underpinned by innovation relevant to specific problems. We would need to understand how technology is changing primary care delivery and why a well-functioning primary care model would cut the overall cost of healthcare delivery and decrease the pressure on secondary and tertiary care. The reason being the emphasis of a well-run health system is to keep the population healthy with constant checks to prevent hospitalisation. In essence, we would have to change the health story we are telling in our heads and force the narrative. I believe this is feasible and must be led by civil society groups and the media. The story the politicians tell us sucks but we continue to believe it because we can relate to it. If we want the story of our health delivery to change, we simply have to start from our dreams and be demanding of utopia.

By Kwame Sarpong Asiedu