Another historic election in Ghana, but not much would change after

Since Ghana adopted constitutional democracy in 1992, every four years after that have marked momentous events as political parties and individuals compete for votes in presidential and parliamentary elections. This year isn’t any different, it comes with its own unique set of expectations. There are 12 presidential candidates, but only two are actually in the race.

Since Ghana adopted constitutional democracy in 1992, every four years after that have marked momentous events as political parties and individuals compete for votes in presidential and parliamentary elections. This year isn’t any different, it comes with its own unique set of expectations. There are 12 presidential candidates, but only two are actually in the race.

And irrespective of who wins, the tenets of democracy, such as freedom of speech, expression and the media would continue to sway.

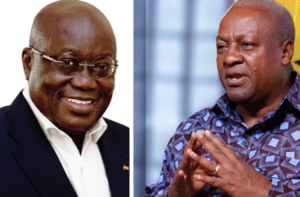

The presidential election is between the two main candidates; incumbent President Nana Akufo-Addo of the New Patriotic Party (NPP), and the man he defeated and made a one-term president in the 2016 elections – John Mahama of the National Democratic Congress (NDC).

Whoever wins the election set for December 7, 2020, will be making history. If Akufo-Addo loses, he would be the second one-term president in Ghana’s democratic experience and oldest president at 76 years, and if Mahama wins, he would have made history as the only president to have lost any election and made a comeback four years later.

Over 17 million Ghanaians are eligible to vote. The voting will take place across the country in 33,367 polling.

Mahama is on a “rescue mission”, while Akufo-Addo wants four more years to do more.

Mahama is believed to have lost the 2016 election on the perception of corruption in his government, and while corruption has been common in the Akufo-Addo government, ironically, corruption perception hasn’t come up strongly in the campaign.

Most pollsters have projected Akufo-Addo to win the election, but as recent history has shown, particularly with the US election of 2016 where Donald Trump was consistently shown to be losing to Hilary Clinton, he eventually won the election, making nonsense of all the polls.

This is also one election in which an incumbent isn’t 100 per cent certain of winning and the closest challenger, isn’t also absolutely certain of wrestling power.

While Ghana’s democratic process has endured, it has largely remained an election-driven phenomena. Often, the elections are peaceful with little or no violence, and hand-over of power has always been smooth.

But once a government takes over the reins of political power, nepotism, abuse of power and abuse of office become commonplace.

Even though a democracy, state security agencies overstep their powers and subject the civilian population to abuse with little recourse to justice. Members of the police and military clearly in most cases don’t seem to operate within their constitutionally mandated boundaries, their excesses, against the civilian population are overlooked and not duly punished or reprimanded.

There is little or no transparency nor accountability, especially when it comes to how revenues from the country’s major exports of oil, cocoa and gold are used. State institutions established to hold the government to account are often ignored, and with no power to bring government appointees to book, they simply bite their nails in despair.

Despite a constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech, expression and association, people are often punished by those who wield power for self-expression – it is common to find for instance on social media, people working in the office of the president gag other citizens for speaking up on issues.

The Ghanaian media is believed to be vibrant – but it isn’t independent. The structure of media ownership places restrictions on journalists and what they can or cannot publish. State security operatives are able to order editors to stay off stories and journalists can’t and often stay away from writing critically about the military. For instance, journalists don’t seem to report on defence expenditure, contractors and sources of military arms and ammunitions. In the past, the military has detained journalists and editors for uncovering matters related to the military. Such matters are often put under the blanket of national security. So effectively, if there is corruption in military procurement, the media in democratic Ghana won’t be too enthusiastic in reporting it.

Elections in Ghana have become more about who wins an election and wields power, and not about democratic principles.

Therefore, irrespective of who wins the 2020 elections, the democratic principles of justice, transparency, accountability, free speech and media will continue to wobble.

By Emmanuel K. Dogbevi