Shadow Diplomats: The shady world of Honorary Consuls

Honorary consuls are meant to foster ties between countries. But criminals and others accused of exploiting the position have infiltrated their ranks.

After jetting into Accra, the capital of Ghana, the international arms broker who called himself “Excellence” greeted his buyers at the Golden Tulip Hotel now renamed Lancaster Accra, and proposed a secret sale: millions of dollars in missiles and grenades for use against American forces.

After jetting into Accra, the capital of Ghana, the international arms broker who called himself “Excellence” greeted his buyers at the Golden Tulip Hotel now renamed Lancaster Accra, and proposed a secret sale: millions of dollars in missiles and grenades for use against American forces.

“Who else knows I’m with Hezbollah?” Faouzi Jaber asked as night fell on the four-star hotel with a life-sized sculpture of a giraffe in the lobby.

Jaber, who was representing a top operative for the Iran-backed terrorist organization, offered to sweeten the deal. He would help the buyers secure coveted positions as special diplomats — known as honorary consuls — who can travel easily through airports and transport their bags without law enforcement scrutiny.

“I will make you a consul in your country,” Jaber said. “All of your friends will be consuls because when we travel —” His associate cut in: “You’ll have a diplomatic pass.”

“I will make you a consul in your country,” Jaber said. “All of your friends will be consuls because when we travel —” His associate cut in: “You’ll have a diplomatic pass.”

Jaber’s covert offer in the fall of 2012, recorded and transcribed by federal investigators, promised protection through a little-known international programme that gives countries large and small the ability to enlist private citizens to serve as volunteer diplomats around the world.

Founded centuries ago, the honorary consul system was meant as a lifeline for countries unable to afford foreign embassies but has since broadened into a mainstay of international relations, embraced by a majority of the world’s governments.

Unlike ambassadors and other professional emissaries, consuls work from their home countries, drawing on connections and clout to promote the interests of the foreign governments that appoint them. In exchange, consuls gain entry into the lofty world of diplomacy and receive some of the same protections and perks provided to career diplomats.

Under an international treaty, their archives and correspondence cannot be seized. Their consular “pouches” — bags, boxes and shipping containers of any weight and size — are protected from searches. The title and swag, including special passports and license plates, can open doors in industry and politics.

But corrupt, violent and dangerous appointees, including those accused of aiding terrorist regimes, have turned a system meant to leverage the generosity of honorable citizens into a perilous form of rogue diplomacy that threatens the rule of law around the world.

A first-of-its-kind global investigation by ProPublica, and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists identified at least 500 current and former honorary consuls who have been accused of crimes or embroiled in controversy. Some were convicted of serious offenses or caught exploiting their status for personal gain; others drew criticism for their support of authoritarian regimes.

A first-of-its-kind global investigation by ProPublica, and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists identified at least 500 current and former honorary consuls who have been accused of crimes or embroiled in controversy. Some were convicted of serious offenses or caught exploiting their status for personal gain; others drew criticism for their support of authoritarian regimes.

These numbers are almost certainly an undercount — no international agency tracks honorary consuls, and dozens of governments don’t publicly release their names.

ProPublica and ICIJ found that convicted drug traffickers, murderers, sex offenders and fraudsters have served as honorary consuls. So have weapons dealers and those who have advanced the interests of North Korea, Syria and other corrupt governments.

Thirty honorary consuls have been sanctioned by the United States and other governments, including 17 who were designated while they held their posts. Some were members of President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle blacklisted after Russia invaded Ukraine earlier this year.

Unlike ambassadors and other professional emissaries, consuls work from their home countries, drawing on connections and clout to promote the interests of the foreign governments that appoint them. In exchange, consuls gain entry into the lofty world of diplomacy and receive some of the same protections and perks provided to career diplomats.

Nine honorary consuls identified by ProPublica and ICIJ have been linked to terrorist groups by law enforcement and governments. Most were tied to Hezbollah, a political party, social services provider and militant group in Lebanon designated by the United States and other countries as a terrorist organization.

Hezbollah’s attacks in Israel, Argentina, Lebanon, Iraq and elsewhere have wounded and killed hundreds, including 241 U.S. Marines, sailors and soldiers who perished during a 1983 peacekeeping mission in Beirut when a suicide bomber drove a truck packed with explosives into their barracks. Earlier this year, a Hezbollah operative was convicted in New York for receiving weapons and bomb-making training from the organization and casing targets for future attacks, including the Statue of Liberty and Times Square.

Former U.S. officials who have investigated Hezbollah’s financial network said the use of honorary consul status by the terrorist group is intentional, well organized and woefully unexamined. In March, the Treasury Department sanctioned a prominent businessman in Guinea, accusing him of funneling money to Hezbollah and using his honorary consul status to move in and out of the country with little scrutiny.

“Hezbollah has realized that if they use these honorary consuls … they can basically move stuff with impunity and no one is ever going to bust them — you flash your diplomatic passport, no questions asked,” said David Asher, a former senior counterterrorism finance adviser for the Department of Defense assigned in 2008 to help oversee a federal investigation of Hezbollah’s criminal network. “It’s a huge seam in our international law enforcement capabilities sweep.”

To identify terrorist operatives and other honorary consuls accused of wrongdoing, ProPublica and ICIJ reviewed court records, government and public policy reports and news archives from six continents. Reporters from more than 50 international media organizations and student journalists from Northwestern University also probed cases.

Some of the identified consuls were accused of wrongdoing previously and named to their diplomatic posts anyway. The majority of the consuls drew scrutiny while they held their positions.

In North Macedonia, intelligence officials found that two consuls allowed their offices to be used as a base for a Russian propaganda operation aimed at limiting the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Both consuls have denied wrongdoing.

In Myanmar, a consul sanctioned by the U.S. and other governments reportedly used his connections to help supply weapons to the brutal military junta during its genocidal campaign against ethnic minorities. The consul could not be reached for comment.

Once accused, some consuls have tried and sometimes successfully dodged criminal inquiries through bogus assertions of sweeping legal immunity that have confused or obstructed police and prosecutors.

The lawlessness and claims of impunity have largely been met with silence: Few governments have publicly called to put safeguards in place, despite warnings from law enforcement and others.

“Consuls act completely autonomously and are not controlled by the State they represent. … The Spanish government has no chance of intervening in their affairs,” investigators in Spain wrote in a confidential 2019 report about three honorary consuls under investigation for laundering money for a suspected drug trafficker.

The handful of governments that have stepped in, including those in Canada, Bolivia, Costa Rica and Montenegro, have reported lapses in oversight or dangerous breakdowns. Liberia once dismissed nearly all of its honorary consuls, citing reports of criminal activity.

After reporters raised questions, Germany and Austria dismissed a consul in Brazil. Another in Switzerland announced his resignation.

Thousands of honorary consuls remain active around the world, though there is no reliable count or any way to determine how often they break laws or abuse their privileges.

Retired Drug Enforcement Administration supervisory special agent Jack Kelly, who helped bring Jaber to justice, worries that dangerous consuls go undetected.

“What people actually do with that diplomatic immunity,” Kelly said, “most of the time we’ll never really know.”

A system to empower and protect

Honorary consuls date back at least to the fall of the Western Roman Empire, when Greece, China, India and countries in the Middle East appointed volunteer foreign liaisons to expand commerce. The arrangement caught on around the world.

In the United States, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson in the late 1700s referenced the use of consuls —one in London was tasked with intelligence gathering, records and studies show.

The U.S. government, however, stopped appointing its own honorary consuls overseas in 1924, opting to rely exclusively on career diplomats. It was a prescient move: Three years later, an international panel warned that awarding special advantages to private citizens enabled them to compete on an “unfair basis” with business rivals.

Honorary consuls, the panel said, should “no longer exist,” adding that most “are far busier with their personal affairs than with those of the country which has conferred the title upon them.”

Concerns about exploitation mounted, according to hundreds of pages of notes and documents from the United Nations archives. In 1960, an expert on the subject appointed by the United Nations warned that honorary consuls were not subject to disciplinary controls in the same way that career diplomats were.

Still, when dozens of governments gathered a few years later in Vienna, they enshrined in international law a valuable set of benefits that included few protocols for oversight.

Under the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, honorary consuls were guaranteed the “freedom of movement and travel” in the countries where they served. They could communicate without restraint, their consulate records and correspondence protected from searches and their offices protected from “any intrusion … or impairment of … dignity.”

Consuls received legal immunity in matters involving their work. Though immunity was not extended to unrelated offenses, the treaty stipulated that honorary consuls would be entitled to criminal proceedings “with the minimum of delay” and “the respect due … by reason of his official position.”

Some countries, troubled in part by the secrecy rules for consular pouches — which can be moved by plane, train, car, ship or courier — insisted they would not protect them. Other countries have opted out altogether, declining to appoint or receive consuls.

But diplomacy is a delicate affair: Restricting another country’s representatives, volunteer or otherwise, can produce a reciprocal response. The vast majority of countries have signed on, and though some apply privileges and immunities differently in practice, the overarching rules have remained unchanged in the nearly six decades since.

Honorary consuls say they do valuable work for little or no pay and want to rid the system of abuse.

“Does it worry me? Absolutely it does,” said Louis Vella, who represents Malta in California and oversees a national association of foreign and honorary consuls in the United States. Vella has greeted visiting dignitaries and supported Malta’s Special Olympics team when it competed in Los Angeles.

“If you have a bucket of nice Granny apples and you put in a bad one, the Granny apples are going to be very upset,” he said. “It’s very bad because of the tainted image that it will give to everyone else.”

Last year, the U.S. State Department pressed states to stop issuing vanity license plates to honorary consuls to prevent “further fraud or abuse.” The department pushed back, however, when members of Congress years ago cited terrorism concerns and recommended reviewing the use of diplomatic bags.

The worry among those who have long questioned the honorary consul system is that countries anywhere in the world can put a diplomatic shield around private individuals thousands of miles away simply by naming them consuls.

Honorary consuls say they do valuable work for little or no pay and want to rid the system of abuse.

The title has become so coveted that an industry of online consultants emerged, promising to deliver honorary consul appointments from impoverished countries for tens of thousands of dollars in fees.

“Travel through diplomatic channels as a VIP-person, often with visas,” one international company, Elma Global, boasts online, saying that perks can include no “annoying customs checks” and “unlimited entry and exit privileges.”

“It’s just amazing that you can become the honorary consul tomorrow, if you want to and you’re willing to pay the money,” said Bob Jarvis, an international and constitutional law professor at Florida’s Nova Southeastern University, who has argued for overhauling the system for almost 40 years. “People buy these things or get them as a reward for supporting a political candidate, and people have no idea what they are supposed to be doing. And no one is busy checking them out.”

Elma Global said in a statement that it does not guarantee honorary consul appointments, adding, “We know that there is much scam on the Internet regarding the honorary consul or diplomatic appointments but we are very far from that.”

Around the world, media outlets and governments have occasionally described isolated incidents of wrongdoing among consuls. ProPublica and ICIJ compiled the most comprehensive accounting to date, including consuls identified in criminal or civil cases that have never been publicly reported.

The investigation, which included cases of consuls scrutinized individually or through their affiliated companies, also drew on findings from human rights groups, the United Nations, anti-corruption watchdogs and media organizations. ProPublica and ICIJ were able to identify 57 consuls who were criminally convicted while holding their positions.

The reporting not only showed how frequently the volunteer diplomats get into trouble but also how widely they have exploited their status.

Consuls have invoked diplomatic credentials to avoid searches and arrests — even to avoid tax bills and parking fines. They have stood accused of hiding cash and contraband in their offices and pouches.

One former consul in Egypt was convicted of attempting to smuggle more than 21,000 antiquities out of the country in a diplomatic container, including mummy masks and a wooden sarcophagus, a coffin used by ancient civilizations to honor their dead. Ladislav Otakar Skakal, who was sentenced in absentia to prison, could not be reached for comment.

The use of the system by terrorist financiers and supporters, experts say, is most alarming, presenting an immediate threat to the United States and countries around the world.

“This honorary consul thing — that’s the theme,” said former DEA supervisor Kelly, who spent a decade investigating Hezbollah until his retirement in 2016. “It shows a real organized approach to how you’re conducting your activity in Africa and probably around the world.”

“You are the Consul Official”

Kelly knew very little about honorary consuls in late 2008, when numbers on a cellphone being tracked by the U.S. government led him to an elusive Lebanese businessman who would quickly become a top DEA target.

Kelly was helping to lead a federal operation known as Project Cassandra, established to dismantle Hezbollah’s sprawling criminal empire. From a cubicle in a secret government facility in Chantilly, Virginia, Kelly had studied contacts on a phone used by a Hezbollah envoy suspected of helping to advance Iran’s secret nuclear and ballistic missile programs. Kelly eventually settled on a single phone number in Lebanon.

The number was for Mohammad Ibrahim Bazzi.

“‘Hey, I got this guy. He’s got to be incredibly significant,’” Kelly recalled telling Asher, the Department of Defense adviser who was also overseeing Project Cassandra.

Kelly and Asher suspected that Bazzi was a top Hezbollah financier closely affiliated with the Iranian regime who was laundering illicit money through his companies in Lebanon and Africa.

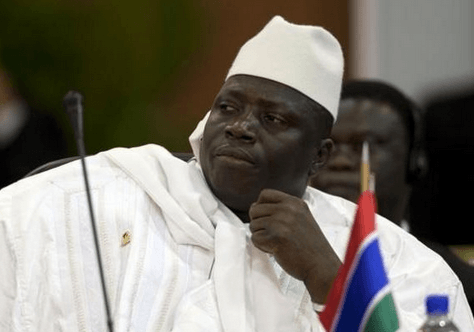

In Gambia, Bazzi was a petroleum importer and associate of Yahya Jammeh, a former Head of State accused by a Gambian government panel of kidnappings, rape, murder and torture. Jammeh has denied wrongdoing.

Kelly and his colleagues were focused on Bazzi’s alleged criminal activities but eventually discovered that Bazzi was an honorary consul, appointed by the government of The Gambia in 2005.

Bazzi presented himself as a consul in 2017 when he stood before the Gambian government panel, accused of paying bribes to Jammeh and contributing to what officials called the “near ruin” of the country. Gambian officials said that Bazzi’s honorary consul status had been revoked several months earlier.

“He had no respect for Gambians or Gambian institutions,” authorities concluded in a final report. “In his quest for wealth, he focused only on profits mostly unlawfully obtained.”

That same year, Bazzi sought to install his son as a consul because he could “exert his influence” over him, according to the U.S. Treasury Department.

Though Bazzi was never criminally prosecuted in the United States, he was designated a Hezbollah financier and sanctioned in 2018. His son was sanctioned one year later for allegedly working on his father’s behalf.

An attorney for Bazzi declined to respond to questions and Wael Bazzi could not be reached for comment. In 2019, the men separately sued the U.S. government, seeking to overturn the U.S. sanctions. In court records, Bazzi said the government exaggerated transactions and events that had occurred years earlier and failed to provide evidence that he financed Hezbollah.

Bazzi said that one of his duties as honorary consul was to “strengthen foreign investment ties between Lebanon and The Gambia” and that he ended his relationship with Jammeh in 2016 after a series of threats. He also said he had previously agreed to work as an informant for the U.S. government and was told that he would not be sanctioned.

In 2020, a federal judge dismissed the lawsuit brought by Bazzi’s son. Last year, Bazzi settled his own lawsuit with the U.S. government. Bazzi and his son remain under sanctions, and the State Department is offering a reward of up to $10 million for information on Bazzi and others that leads to disruption of Hezbollah’s financial network.

As Project Cassandra pushed forward, honorary consul status emerged again — this time during the operation that netted Jaber, the Hezbollah-affiliated arms broker who met with buyers at the hotel in Ghana in 2012.

The buyers were DEA informants posing as representatives of an internationally known guerrilla group in Colombia seeking to overthrow the government and strike at the U.S. forces stationed in the country.

“We fight against Americans … they are invading my country,” one informant told Jaber, according to a transcript of the conversation obtained by ProPublica and ICIJ and described in a subsequent indictment. “What we need exactly … is a good person that can provide us with weapons.”

“Hezbollah sells,” Jaber said. “… What kind of weapons?”

“You know, M14, M16?” the informant said, referring to rifles. “Grenades, pistols, rifles.”

“Explosives,” Jaber said. “Dynamite and stuff … pow, pow, pow, pow.”

For protection, Jaber offered consulships, saying, “All the high people, all the rich people, [are] all consular.”

“The best is Africa,” Jaber said, adding that “many European white men work as [consuls]” from their home countries when there are no embassies nearby.

At a second meeting with buyers three months later, Jaber said: “We go to any country in Africa. We make you consul of Equatorial Guinea [or] Guinea-Bissau. … You pay $200,000.You are the consul official of the country. And you have other passport.”

In 2014, Kelly flew to Prague, where another meeting had been planned, to ensure that Jaber, associate Khaled el-Merebi, as well as the DEA’s top target, Lebanese-born arms dealer Ali Fayad, were taken into custody. Fayad and Merebi were later released by the Czech government, reportedly in exchange for five Czech nationals kidnapped in Lebanon.

Jaber, who had promised to supply surface-to-air missiles, assault rifles and grenades, move and store cocaine in West Africa, and launder the proceeds through bank accounts in New York, was extradited to the United States. He pleaded guilty in 2017 to conspiring to support the Colombian terrorist group and was sentenced to prison.

At the hearing, he pleaded for his freedom, saying he was under the influence of drugs at the time and made a “once-in-a-lifetime mistake.”

“I admit that I committed a crime, but I didn’t do it thoughtfully,” he said. “It wasn’t like I was eager to commit that crime. … I’m asking forgiveness from you and from the American nation and from the U.S. government. I do love the American people.”

In an interview from federal prison in West Virginia, Jaber acknowledged offering honorary consul posts but said the U.S. government doctored the transcripts of meetings to “entrap” him. He added that he opposes Hezbollah.

“Honorary consuls, I know how they work, I know how they are created,” he said. “Honorary consuls move drugs, money. I know many honorary consuls who get up to all kinds of foolishness.”

Quest for justice

As the agents of Project Cassandra hunted Hezbollah’s arms and drug traffickers, New Jersey attorney Gary Osen was immersed in accounts of Hezbollah’s deadly campaign against U.S. service members in Iraq.

Osen and his legal team gathered death records, studied battlefield forensic reports and interviewed the families of fallen soldiers. The research turned up references to honorary consuls who had been linked to Hezbollah’s finance networks.

“Everybody who is a big shot in that world is an honorary consul,” he said. “It is not necessary to their operation. But it is a further lubricant.”

In 2019, Osen filed a lawsuit on behalf of more than 1,000 Americans, including members of the military killed or wounded in Iraq by roadside bombs and other weapons that the complaint links to Iran and Hezbollah.

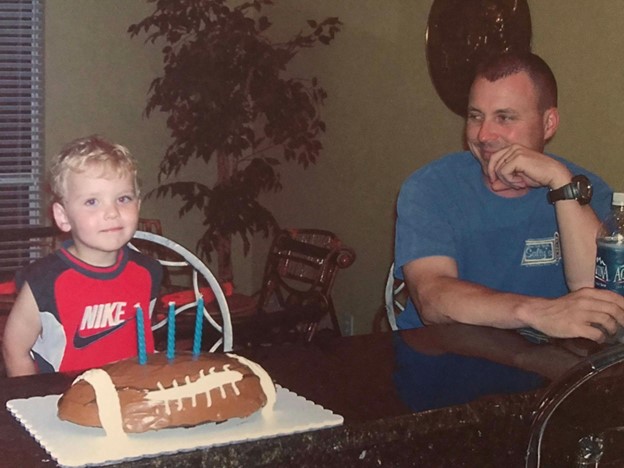

The active case in federal court in New York accuses 13 Lebanese banks of violating anti-terrorism laws by knowingly managing and moving money for Hezbollah during the deadly attacks, including one that killed U.S. Army Capt. Shawn English while he was riding in a Humvee outside of Baghdad in 2006. The father of three had been nearing the end of a 10-month deployment in Iraq

“Is something wrong with Dad?” 7-year-old Nathan English had asked after saluting the two Army officers who arrived at the family’s Florida home to break the news.

The complaint alleges the banks provided “extensive and sustained material support, including financial services, to Hezbollah … and its operatives, and facilitators,” as well as “vital access to the United States financial system.”

The banks have denied wrongdoing, saying in court documents that they “categorically abhor terrorism and all unjustified acts of violence. But they are not legally or factually responsible for plaintiffs’ battlefield injuries.” The banks also said the complaint did not identify transactions for anyone connected to Hezbollah.

Fransabank in Beirut, one of the lenders named as a defendant in the lawsuit, was acquired by Adnan Kassar and his brother, Adel, who has served as the bank’s deputy chairman and CEO and has been Hungary’s honorary consul in Lebanon since at least 2002, records show.

Bazzi, the sanctioned former honorary consul for The Gambia in Lebanon, held an account at Fransabank and another Lebanese bank named in the case, according to Osen’s complaint.

“It’s dirty money. At what cost? How many lives?” said retired Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bartlett, a plaintiff in the case.

Like English, according to court documents, Bartlett and his convoy in Iraq were struck by a particularly lethal variation of a roadside bomb known as an explosively formed penetrator, or EFP.

The bomb in 2005 cut through the door of Bartlett’s Humvee, shearing his face from temple to jaw as smoke choked the vehicle and diesel spilled to the ground. The staff sergeant next to him was decapitated and the gunner between them would lose his legs. Bartlett, 31 at the time, has since had 40 medical procedures, including 12 major surgeries, and managed to regain some function in his face, body and hands.

“The devil wanted me dead,” he said.

The Kassar brothers and Fransabank did not respond to requests for comment.

A power center for Consuls

In Lebanon, where Hezbollah operates as a major political party, a provider of popular public services and a feared militia force, honorary consul titles are widely considered a sign of status.

“It’s something like lordships in the British system,” said Mohanad Hage Ali, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. “If you have a connection to another sovereign state, whether you know the president or someone in his entourage, you get this honorary consul title. It’s one Lebanese way of saying, ‘I’m important.’”

One writer for a Hezbollah-affiliated newspaper in 2015 quipped in a column titled “The Homeland of the Consuls” that becoming a consul in Lebanon is secured first by “finding an independent island beyond an ocean that no one may have heard of. Second, discovering the most appropriate way to reach its king: a rare diamond, a Rolex watch, or tens of thousands of dollars a year.”

One of Lebanon’s honorary consuls is Ali Myree, nominated by South Sudan in 2019.

Born in Lebanon, Myree was living in Paraguay in 2000 when he was charged with pirating CDs, video games and software. Authorities suspected he was funneling some of the proceeds to Hezbollah, according to Paraguayan media reports.

When police raided his apartment, they reportedly found film footage of terrorist attacks and interviews with suicide bombers, including a CD of a radical leader who pressed listeners to strike the United States and Israel.

Myree left Paraguay and eventually reemerged in South Sudan, where he became a prominent business leader in the long-troubled country. Myree struck a mining partnership with the president’s daughter and sent a series of payments to a general sanctioned by the United Nations Security Council and others for destabilizing the country, according to a 2021 report by The Sentry, a Washington, D.C.-based group that investigates the financing of armed conflict.

Myree was nominated to become the country’s honorary consul in 2019.

“Since the first day we had assumed this responsibility and trust,” Myree said during a celebration of the consulate’s opening in Beirut, where he posed with diplomats and a white cake that bore the flags of both countries.

Myree, who has noted that his motto in life is “the sky is the limit,” denied in a statement ever having a relationship with any terrorist organization. Myree said that piracy was common in Paraguay at the time of his arrest and that he “lacked guidance, education, legal exposure, and experience. … I am also not ashamed of my bad experience, and I do not ignore or hide it.”

He said he was named consul in South Sudan by the country’s president and that his relationship with all of his clients are “merely professional.” “I am proud of the son, husband, father, businessman and honorary consul I am today,” he added.

The Lebanese government did not respond to a request for comment. Neither did a spokesperson for Hezbollah or a local association of Lebanon’s honorary consuls, which published a list of consuls online that included Myree and Fransabank’s Adel Kassar.

That list also included a celebrated businessman in West Africa: Ali Saade.

“To serve Guinea”

In the teeming African port of Conakry, shoeless men haul sacks of rice off the backs of flatbed trucks and stack them floor to ceiling in a cavernous depot owned by the Sonit Group, the company that made Saade one of Guinea’s richest men.

Saade, 80, was born in the impoverished nation on West Africa’s Atlantic coast, but his mother and wife are from Jwaya, one of a string of villages of olive and fig trees south of Beirut that has long been a power center for Hezbollah.

In Guinea in 1992, Saade opened Sonit after working in his father’s textile business. He settled into a pristine neighborhood several miles from the Conakry port, where women smoke sardines on abandoned oil drums and children play with crabs plucked from dirty water.

In 2006, Saade was named by the government of Guinea as its honorary consul in Lebanon, where Saade’s wife and daughter live.

Earlier this year, the U.S. government alleged that Saade and another prominent businessman in Guinea, Ibrahim Taher, were key Hezbollah financiers. The government also noted that Taher was an honorary consul for Lebanon in Cote d’Ivoire and used his status to travel in and out of Guinea with “minimal scrutiny.”

Saade stands accused of initiating money transfers from Guinea to Hezbollah and providing “unrestricted access” to the highest levels of the Guinean government for Kassim Tajideen, who was sanctioned by the United States in 2009 for financing Hezbollah. Tajideen was later imprisoned in Maryland for violating the sanction by helping to move more than $1 billion through the U.S. financial system. In 2020, he was released and sent back to Lebanon. He could not be reached for comment.

The U.S. government also alleged that Saade, Taher and others traveled in 2020 to Lebanon on a special flight with a “large amount of money” that the group claimed was for COVID-19 relief. The coronavirus had been used before as a cover for transferring funds from Guinea to Hezbollah, authorities said.

Both men were sanctioned in March.

After the sanctions, prosecutors in Guinea launched a criminal investigation.

In an interview, Saade said he acted in his capacity as honorary consul when he connected Tajideen to Guinea’s former president.

“‘Listen, Ali, as honorary consul you should do something to encourage investment,’” Saade recalled the former president saying.

Saade said he did not know that the U.S. had sanctioned Tajideen. In a statement, Saade added that he carried only $800 when he flew to Lebanon with Taher and others in 2020. “I never gave or transferred one dollar to Hezbollah,” Saade said.

Taher, 59, did not respond to requests for comment. He has previously denied the allegations, saying in a statement that he has no connection to Hezbollah and has “never used any illegal means to transfer funds out of Guinea.” He also said he has never been an honorary consul.

In July, an appeals court judge in Guinea closed the criminal investigation into Taher and Saade, saying there was no evidence of terrorism financing. The judge also pointed to a Guinean government investigation showing that Taher was not an honorary consul.

Guinean authorities have appealed the court’s ruling on Saade and Taher, according to an official.

Saade said that the Guinean government suspended his honorary consul status after the U.S. sanction but that he’s not concerned about what comes next. He said he met with Guinea’s new president shortly after the sanctions were announced.

“He reassured me that there will be no acts of injustice,” Saade said. “I acted as a consul to serve Guinea. It’s to help the country.”

By Debbie Cenziper and Will Fitzgibbonand Delphine Reuter and Eva Herscowitz and Emily Anderson Stern

Fitzgibbon and Reuter are with ICIJ. Herscowitz and Stern are with Northwestern University’s Medill Investigative Lab.

Contributors: Nicole Sadek, Jelena Cosic, Margot Williams, Miriam Pensack, Emilia Díaz-Struck, Benedikt Strunz, Jan Strozyk, Jesús Albalat, Akoumba Diallo, Noel Konan, Diana Moukalled, Emmanuel K. Dogbevi, Saska Cvetkovska, Bernd Schlenther, Sophia Baumann, Jordan Anderson, Hannah Feuer, Michael Korsh, Michelle Liu, Grace Wu, Linus Hoeller, Dhivya Sridar, Quinn Clark and Henry Roach.