Jokes about Chinese goods are not funny anymore

Jokes about Chinese goods are not funny anymore. At least that’s one of the things 2015 has taught us.

Economic growth in the world’s second largest economy slowed to its lowest since the global financial crisis and the attendant reduction in China’s demand for commodities, and subsequent effect on price, hit hard on Africa’s commodity-exporting economies.

According to the Bank of Ghana, the country had lost more than $3 billion in revenue as at October 2015, to the decline in commodity prices, in which its main foreign exchange earners – cocoa, gold and oil – have been affected.

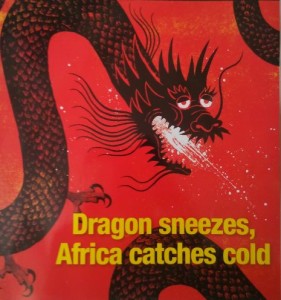

The November issue of The Africa Report bore an image of a sneezing dragon on the front, with the title “Dragon sneezes, Africa catches cold”.

But as The Africa Report’s Nicholas Norbrook wrote in that issue, the fall in commodity prices could be a catalyst for Africa to diversify and transform its economies.

He wrote: “Perhaps this collapse in commodity prices is exactly what Africa needs to turn its attention to the foundation stone of national progress in many economies throughout history: agriculture.

There is a real opportunity here too, with rising appetites and wealth levels in both Africa and Asia, and an extra 2.5 billion mouths to feed by 2050.

Much of the world’s remaining unused arable land and water is in Africa – a comparative advantage that policy-makers need to use to their benefit, not sell off on the cheap.”

But unfortunately, Ghana Finance Minister, Seth Terkper’s optimism seems to be hinged rather on an increase of output in cocoa and petroleum: same old commodities.

“The important thing is not so much about the past but the prospects. The services sector is outstanding. Cocobod [the state cocoa marketing board] says we’ll exceed our target of 850,000 tonnes of cocoa this year and we are going into the next two years exporting more gas and crude oil,” Mr Terkper was quoted as saying by London-based Financial Times (FT).

The share of agriculture in Ghana’s GDP, is on a downward trajectory and has dwindled from 39 per cent in 2008, to 19 in 2015. The growth rate of agriculture, down from 7.4 per cent in 2008, is now at 0.04 per cent, and the crops sub-sector is experiencing negative growth.

In the course of the year, one minority member of parliament questioned why the majority was now mentioning the growth rate beyond the usual one decimal place.

Ghana’s 2016 budget, themed ‘Consolidating Progress towards a Brighter Medium Term’, allocated only one per cent, to agriculture.

Roshni Rajiv, head of the Centre for Climate Change, Agriculture and Environmental Studies at policy think tank Imani, was not impressed.

“The plans and policies for the agriculture sector contained in 2016 budget is more or less similar to old plans and policies included in the previous 2015 budget. The absence of any progressive policies to revive the sector is a mockery of the whole theme of the Budget 2016.”

Either solution to the challenge, boosting agriculture or cocoa and oil production in the hopes that the high output could offset downward pressure on price and reap gains, is significantly hinged on China’s recovery over the next few years.

If China’s economy doesn’t recover swiftly enough, if the goods that we mock are not produced sufficiently enough, and if our industrial growth remains where it is, Ghanaians can be sure that the joke would remain on us.

By Emmanuel Odonkor