Ghana’s e-government public-private partnership and the value of long-term strategies

Most African countries have realized the importance of private investment and are experimenting with private sector partnerships for the construction, maintenance, and/or operation of capital intensive projects. Where they have succeeded, as with Ghana’s e-government public-private partnership (PPP), results benefit the entire society.

Most African countries have realized the importance of private investment and are experimenting with private sector partnerships for the construction, maintenance, and/or operation of capital intensive projects. Where they have succeeded, as with Ghana’s e-government public-private partnership (PPP), results benefit the entire society.

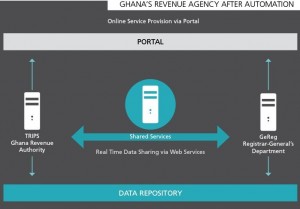

In April 2010, the Government of Ghana signed a public-private partnership (PPP) contract to reengineer business registration processes, deploy state-of-the-art application software and hardware, and employ best-in-class solutions for the Ghana Revenue Authority and the Registrar General’s Office. This was part of a broader program to achieve greater efficiency, transparency, and effectiveness in the delivery of selected government services using information and communications technology (ICT).

The PPP was structured on a design, finance, build, operate, and transfer model. The government supported the project through resources from a World Bank-financed “eGhana Project, contributing about one-third of the $60 million project costs; the private sector contributed the remainder. The agreement was for the private sector to build and manage the e-tax and electronic business registration platform until their investment costs were recovered—within five and not exceeding seven years from the effective date of the contract. At the end of the operations period, the system would be turned over to designated government organizations for continuing operation.

The objective of eGhana was to broaden the tax base, increase compliance and transparency, reduce incidence of fraud, and improve the competitiveness of the business climate in Ghana. The existing processes led to fraud and significant delays; for example, business registration in Ghana before the automation took on average about two weeks. After automation, businesses could complete registration in three to five days, and planned improvements will ultimately reduce this to one day.

Overcoming Challenges

The process of automating Ghana’s revenue agencies and the business registration system faced significant challenges along the way. For example:

* The consultation process to validate the PPP design took over a year.

* A first bid process to select private partners overlapped with the financial crisis, which resulted in potential private partners requesting a greater contribution from the public sector.

* Prices for the second bid were about 40 percent higher than the government had projected.

* A new Ghana Revenue Authority Bill was passed immediately after award of the contract. This required consolidation of the five original revenue agencies into a single Revenue Authority and changed the scope of the awarded contract, though the payment terms remained unchanged.

* Ghana discovered oil, which made any perception of revenue sharing with its private partner politically sensitive, even though the repayment was limited to total cost.

* Protracted World Bank procurement processes added to delays in starting the program. This was due in large part to the World Bank’s rigorous due diligence process, given that the contract was not awarded to the lowest bidder, because the winning bidder had technical superiority.

* Disagreements between private partners and their sub-contractors on intellectual property rights issues delayed implementation.

Despite these challenges, the eGhana PPP is considered a flagship project for the government and one of the more successful PPPs in the country. The tax registration systems are streamlined, and have allowed about 592,000 new taxpayers to file online. The combined impact of new taxpayers and new businesses seeking to normalize operations is already having a positive impact on the revenues of the Registrar General’s department and the economy as a whole.

Modelling Change

Other countries can learn from Ghana’s e-government PPP. In particular, it’s important to keep in mind that the implementation of complex PPPs (especially for tax modernization) requires the utmost commitment of all partners to the broader vision of improved efficiency and services to citizens. It also requires that all partners remain flexible to policy changes that may improve outcomes. Communicating continuously with the public and relevant stakeholder institutions throughout the project implementation process is key as well.

Staying the course brings measurable benefits to all parties. For the government, it includes a broadened tax base, potential increase in revenues, reduced inefficiencies, and cost savings. Taxpayers gain access to new, simplified online services. For the private partner, rewards vary and may include agreed interest on investment or share of revenue collected in other countries. In Ghana’s case, the share of revenue was capped at total cost of investment. There are also rewards for development partners in the form of improved governance and judicious use of scarce public funds.

Ghana’s experience with the e-government PPP provides lessons for other PPP projects in the country. This is particularly important following the country’s adoption in June 2011 of the National Policy on PPPs, as the country moves to put in place the requisite legal framework. The potential benefits of the partnership, including leveraging private capital to complement limited public resources, more efficient public services, and improved national and business competitiveness, provide promising lessons for structuring more PPPs both within and beyond Ghana’s borders.

By Mavis Ampah, Lead ICT Policy Specialist, World Bank & Randeep Sudan, Practice Manager for ICT, World Bank.

Source: World Bank blog