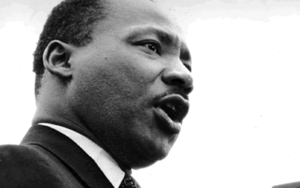

A broader look at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Annual remembrances of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s involvement in the civil rights movement often begin with the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott sparked by the December 1 arrest of longtime NAACP secretary Rosa Parks.

But far less attention is given to those people in Montgomery who labored steadily and anonymously in the months and years before Parks’ refusal to move to the back of the bus – actions that created the conditions in which King could rise to national and international prominence. Bringing those people’s work to light can shift how we understand the character and time frame of social change movements and point a way forward during this precarious moment in our democracy’s history.

A freshly minted PhD. from Boston University, King had been in the city for about a year before Parks’ arrest. Local leaders in the black community tapped him to be the face of the boycott in part because he was relatively unknown.

He didn’t stay that way for long.

Speaking on December 5, King’s baritone voice rose as he assured the thousands of people assembled at the Holt Street Baptist Church of the righteousness of their cause: And we are not wrong, we are not wrong in what we are doing. (Well) If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. (Yes sir) [applause] If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. (Yes) [applause] If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.

The meeting culminated with the formation of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and the election of King as its president. He went on to advocate nonviolence in the face of death threats and the bombing of his house. The U.S. Supreme Court sided with the marchers in November 1956, and the boycotters triumphantly boarded city buses 381 days after the action began. King wrote his first book, Stride Toward Freedom, about the movement.

Yet as significant as King was to the boycott, it would be a mistake only to look at his role to understand its origins and success.

For starters, accounts of Parks often inaccurately portray her decision as a response to being tired after a long day of work. She had attended a workshop at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee that was a site of leadership training for southern civil rights activists four months before her arrest. Far from a passive actor, she was taking a conscious decision against the oppressive Jim Crow system that had been given federal sanction by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision that permitted the doctrine of “separate but equal” to be the law of the land.

“I had been pushed around my entire life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it anymore,” Parks wrote in cursive letters on yellow paper in autobiographical notes in the Library of Congress.

She was not the only person to arrive at the same conclusion.

Claudette Colvin had gotten arrested nine months earlier for the same offense.

“My head was just too full of black history, you know, the oppression that we went through,” she said in a 2009 NPR article. Yet the detention of Colvin, then just 15 years old, did not generate the same level of support from leaders of Montgomery’s African American community. Colvin said on NPR that the NAACP and all the other black organizations felt Parks would be a good icon because “she was an adult. They didn’t think teenagers would be reliable.” She added that Parks’ skin texture was the kind that people associate with the middle class. (Colvin’s skin was darker than the light-skinned Parks.)

E.D. Nixon, a longtime activist and the president of the local NAACP chapter, was one of the leaders of Montgomery’s black community. Despite his failure to back Colvin, he helped organize the boycott after Parks was arrested. King hailed Nixon as “one of the chief voices of the Negro community in the area of civil rights,” and “a symbol of the hopes and aspirations of the long oppressed people of the State of Alabama.” Nixon continued fighting for social justice after the boycott’s conclusion until his death at age 87, concentrating toward the end of his life on housing and organizing programs for African American children, according to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

Nixon collaborated in the 1950s with JoAnn Robinson, president of the Women’s Political Council (WPC), which had been working to address abuses within the bus system for years. In 1949, Robinson had tried to organize a protest after being verbally attacked by a bus driver for sitting in the “Whites only” section of the bus. While she was not successful in mobilizing the WPC at that point, the group did later lodge complaints with city officials, gaining concessions that softened, but did not eliminate, the segregated system. Robinson told the city’s mayor that a bus boycott could come after the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court held that segregation was inherently unequal.

A protester more than a decade before Parks and Colvin, Pauli Murray became an unknowing architect of the legal approach that overturned Plessy. In her memoir, Song in a Weary Throat, she describes how

she and Adelene McBean, her roommate, were arrested in 1940 and charged with disorderly conduct after refusing to obey bus driver Frank W. Morris’ directive to move to the back of the bus.

The NAACP initially defended the women, but decided not to risk an appeal when the court convicted the pair of creating a disturbance, rather than of violating segregation laws. While Murray described McBean and her as a casualty in “the long, hard struggle to outlaw segregation, she did draw a valuable lesson from the experience. “Although we had lost the legal battle, the episode convinced me that creative nonviolent resistance could be a powerful weapon in the struggle for human dignity,” she wrote.

She applied that knowledge four years later.

One of a handful of female law students at Howard Law School, Murray challenged the method the NAACP Legal Defense Fund had employed for years. Rather than incrementally chipping away at segregation by arguing that the separate facilities established under Plessy were not equal, she advocated making a direct attack on the system’s underpinning. “The time had come to make a frontal assault on the constitutionality of segregation per se,” she wrote.

She bet her professor, Spottswood Robinson, ten dollars that Plessy would be overturned within the next quarter century. The result took a decade, and Murray’s final law school paper was part of the successful strategy. When Robinson joined Thurgood Marshall and other lawyers working on the Brown case, he retrieved the document and shared it with his colleagues, who incorporated it in the case briefs.

For his part, Bayard Rustin had been active in civil rights struggling stretching back to 1937 and his efforts to defend the Scottsboro boys, nine black teenagers falsely accused of raping two white women aboard a train near Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1931.. After helping to form the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Rustin served time in prison from 1944 to 1946 because of his violation of the Selective Service Act. Rustin, who met King in 1956, helped deepen King’s understanding and practice of nonviolence. Rustin eventually became one of King’s most trusted advisers and played a pivotal role in planning the 1963 March on Washington.

These are just some of the many people who toiled in different arenas, in some cases over several decades, before Parks’ arrest and King’s ascension. Sometimes working in parallel areas and other times in tandem, their largely anonymous efforts met with mixed results but played an indispensable role in laying the foundation for the Montgomery boycott. Their lives and work are relevant not just to adjust our understanding of Dr. King from one that exclusively celebrates a great American to a more decentralized vision that views him as a tall tree in a full forest. Rather these people’s work also invites us to extend our view of a single precipitating incident to take a deeper look at the grassroots organizing that had been going on largely out of public view in the years preceding the catalytic event.

This vision of a broader swath of people working to bring about change for years before it occurs can also guide as we navigate this troubled period in our nation’s history. Our lengthy list of challenges includes dealing with the worst phase yet of the COVID-19 pandemic, searing economic inequality, and grappling with the devastating impact of systemic racism. Perhaps the most serious: dealing with the aftermath of the recent armed insurrection on the U.S. Capitol incited by President Trump and enabled by Republican leaders. This event was also the product of years of work by thousands of people, many of whom hold a dramatically different vision of truth, science, democracy and the world.

Optimism lies in the senatorial victories in Georgia of Jon Ossoff and the Rev. Raphael Warnock, pastor of the same Ebenezer Baptist Church where Dr. King, his father, and maternal grandfather stood astride the pulpit for more than 70 years. Like the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Warnock and Ossoff’s successes were the result of close to a decade of work by Stacey Abrams and thousands of others across the state working to break the Republican stranglehold on political power.

We can also gain strength from the uprising of millions of Americans who stood up in the wake of George Floyd’s murder on a Minneapolis street and demanded that our country be true to its creed. Powered by youth of all backgrounds, and organized in a decentralized fashion by many who had been working on justice issues in the Black Lives Matter movement since Mike Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson in 2014, these Americans have accomplished meaningful change in many sectors of our society.

Our nation’s ultimate direction is far from certain.

But what is abundantly clear is that the daily actions of millions of people across our nation over the upcoming months and years will shape it as least as much as those of venerated leaders like King and iconic figures like Parks.

By Jeff Kelly Lowenstein

Author is Padnos/Sarosik Endowed Professor of Civil Discourse at Grand Valley State University and the founder and executive director of the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism.