Half of South Africa’s sewage treatment systems are failing – Report

When he was 13 years old, Rudy Hanse joined the guppy development program offered by the Milnerton Canoe Club in Cape Town. There he learned how to paddle a canoe and swim.

For Hanse, the weekly outing to the Milnerton Lagoon was a way to escape the poverty and cacophony of Dunoon township, where he lived with his parents. A taxi, organized by the canoe club, would pick him and other kids up to spend a few hours on the water each week.

It wasn’t canoeing that initially attracted him, but the opportunity to escape the township.

“From the outside it was a sport to do, a way to get out,” said Hanse. “It took two to three weeks to get used to it, but after two or three months I started joining the master’s group and had to come twice a week to training.”

Later, he took up a lifeguarding course, while continuing to paddle at the club and training with other members for the grueling Berg River Canoe Marathon. After graduating high school, he applied for a lifeguarding job in Dubai. Though Hanse did not get the job, he says it led him to a different job in the hospitality industry.

As a result, Hanse was able to extract himself from the poverty and joblessness that permeates Dunoon and begin earning a decent income in guest services in the United Arab Emirates. “If it wasn’t for [that training course], I wouldn’t be where I am today,” he said.

This opportunity was available because the Milnerton Lagoon was clean enough to swim in. That is no longer the case. For years, the water has been too polluted by sewage to risk children being exposed to it, and the canoe club had to close down its guppy development program about eight years ago.

“Kids should be able to have the same experience I had,” said Hanse.

But this is not an isolated incident of how pollution, caused by sewage infrastructure failure, shuts down opportunities for development and employment. Rivers and water bodies across South Africa have become too polluted for use, and the government is doing an increasingly poor job of addressing the situation.

Nationwide failure

As Anthony Turton from the Centre for Environmental Management at the University of the Free State states, this represents “a tsunami of human waste inundating our rivers and dams, without respite, for more than a decade.”

The Green Drop report itself shows a significant failure in wastewater treatment quality over almost a decade. The number of critical treatment works listed in the last report – from 2013 – was 248. The latest Green Drop report, released on March 30, 2022, reveals wastewater compliance has plummeted in the intervening years. Of 850 municipal wastewater treatment works, 334 (39%) are in a critical state, obtaining a score of 30% or less.

“This decline is at both the treatment and sewer collection levels,” states the report. It is not just that wastewater treatment works are failing to properly treat sewage before releasing it back into the environment, much of it is spilling into the environment before even getting to the treatment works.

The average Green Drop score across all provinces in 2013 was 61%. This year, the average score was 50%, indicating that about half of raw sewage and industrial waste is not being treated to standards which are themselves inadequate, according to scientists in the fields of chemistry and epidemiology.

But analysis of the Department of Water and Sanitation’s (DWS) own data shows that even some of the few wastewater treatment works which received scores of 90% or more are polluting the environment.

In addition to the cost it has on youth development programs like the one in Milnerton, this issue is resulting in massive biodiversity losses due to pollution of rivers and estuaries, with a knock-on impact on local economies and livelihoods. Ongoing sewage pollution flowing into the Vaal River, a water source for some 19 million people, is also endangering people’s health, states the South African Human Rights Commission.

The Green Drop score drop

Key to understanding this report and its implications for the health and welfare of South Africans is the acronym NMR, which stands for “no monitoring required.” This means a wastewater treatment works is exempt, according to DWS authorization, from having to comply with all or some effluent quality indicators. While NMR is not reflected in the national Green Drop report, it is found in the individual provincial reports.

Green Drop scores for wastewater treatment works and the sewage infrastructure servicing them are obtained using an equation in which weightings are given to five key performance areas: capacity management; environmental management; financial management; technical management; and effluent and sludge compliance, which, at 30%, has the highest weighting. The report notes, “The effluent quality must comply to 90% [in total] with the authorised limits for the respective categories.”

There are three effluent quality indicators: microbiological compliance, indicating the concentration of fecal bacteria such as E.coli and enterococcus in the water; chemical compliance, indicating the concentration of chemicals such as nitrates and phosphates which negatively impact ecosystems; and physical compliance, indicating turbidity, electrical conductivity and oxygen demand. The minimum compliance levels are set out in the wastewater treatment works’ authorization issued by the DWS.

There are three effluent quality indicators: microbiological compliance, indicating the concentration of fecal bacteria such as E.coli and enterococcus in the water; chemical compliance, indicating the concentration of chemicals such as nitrates and phosphates which negatively impact ecosystems; and physical compliance, indicating turbidity, electrical conductivity and oxygen demand. The minimum compliance levels are set out in the wastewater treatment works’ authorization issued by the DWS.

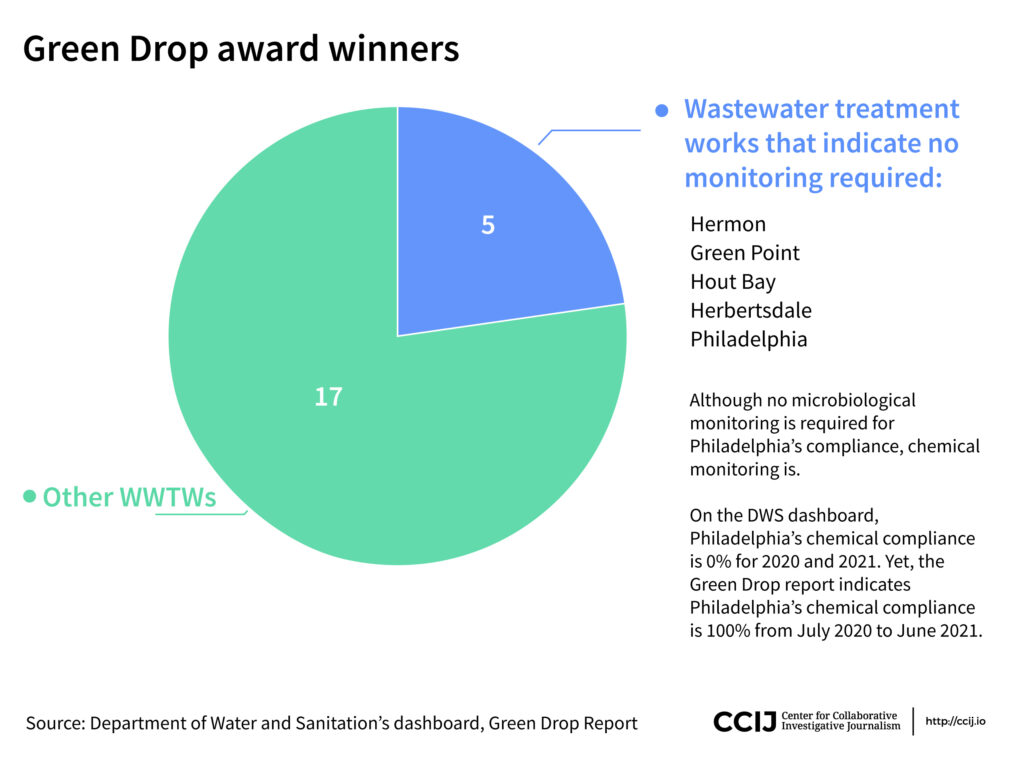

Five of the 22 Green Drop award winners fall into the NMR category, meaning they are exempt from certain effluent quality indicators. All of these are in the Western Cape, which obtained 12 Green Drop awards.

The Green Point and Hout Bay wastewater treatment works in the city of Cape Town, both NMR recipients, are Green Drop award winners. They are also marine outfalls, which means the only treatment the sewage receives before being pumped into the ocean is maceration through a three millimeter sieve to remove solids and grit. Neither of these facilities is required to monitor or reduce the fecal bacteria in the wastewater before releasing millions of liters of sewage into the ocean per day.

This has the potential to negatively affect tourism in Cape Town and the Western Cape which, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, brought in R23 billion ($1.3 billion) in direct spending, creating 300,000 jobs in the province.

Retired town planner and frequent visitor to Cape Town from the United Kingdom Gill Griggs forwarded a letter she had written to the City of Cape Town after witnessing sewage wash up onto the beaches in the vicinity of the Green Point outfall. Griggs stated she was “greatly saddened and disgusted this year to see the beautiful beaches covered in sewage.”

“We had planned… to bring all the family out next year, but with five young grandchildren we are reconsidering, as the sea and beaches are not fit for children to play on,” she wrote.

Griggs’ experience is hardly unusual. Following research conducted by Edda Weimann in 2013, which found Clifton Beach – a drawcard for tourists – contaminated with fecal bacteria, media reports and a public outcry over the marine outfalls led to the city commissioning its own report.

Conducted by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in 2017, it found “no immediate ecological disaster” was imminent as a result of effluent discharge from Cape Town’s marine outfalls. But the report stated that there was “indirect evidence from faecal indicator bacteria counts in seawater samples collected at many sites along the Cape Town shoreline over an extended period that effluent is possibly, even if infrequently, reaching the shoreline.”

The CSIR report noted that although sewage outfalls are common in coastal cities around the world, “the world cannot use the marine environment as a waste receptacle in perpetuity and opportunities for improved and economically and environmentally feasible wastewater treatment, and the feasibility of using alternate strategies for disposing of wastewater to the marine environment should be investigated by the City of Cape Town [and other municipalities].”

The city has stated it has no plans to divert wastewater disposed via the marine outfalls to wastewater treatment works, but it also will not increase the outfalls’ capacity. “Purpose designed marine outfalls were and still are extensively used by coastal cities the world over, and they are still considered an acceptable means of wastewater disposal,” stated City of Cape Town mayoral committee member for water and sanitation, Zahid Badroodien.

Chemicals of emerging concern

Research in 2017, led by University of the Western Cape’s Professor Leslie Petrik, to determine whether sewage pollution was affecting seawater and marine organisms found E. coli counts near the outfalls that were thousands of times above the general limit for treated wastewater effluent.

Besides bacteria such as E. coli, and the nitrates and phosphates which are supposed to be removed during wastewater treatment, Petrik and her colleagues said that the sewage contains chemicals of emerging concern that current wastewater treatment methods, when applied, do not remove.

There are thousands of synthetic chemicals used in pharmaceuticals, personal hygiene products, pesticides and industrial applications. These are stable compounds which do not break down in the environment – but rather accumulate over time.

Petrik and her colleagues tested for 15 of them in the area surrounding the Green Point outfall. They included diclofenac (an anti-inflammatory drug commonly known as Voltaren), sulfamethoxazole (an antibiotic used for a variety of infections), phenytoin (a medication used to prevent seizures), carbamazepine (a medication for epilepsy and bipolar disorder), lamivudine (a drug used to treat HIV and Hepatitis B) and the commonly used paracetamol. These were all found to be present in wet sea sand, and accumulating in marine organisms such as seaweed, sea urchins, starfish and limpets.

Further studies found some of these chemical compounds accumulating in fish in False Bay, on the Indian Ocean side of the city. False Bay receives effluent either directly or indirectly from seven wastewater treatment plants, none of which received Green Drop certification awards.

The largest plant, the Cape Flats wastewater treatment plant, which releases effluent into False Bay, scored 0% for microbiological compliance in 2020 and 2021 from the DWS. It scored an average of 37% for chemical compliance. Yet, inexplicably, it achieved an overall Green Drop score of 85%.

Multiple questions about the discrepancies in these numbers were sent to the DWS via email and phone calls, but no response was received.

Contender status

Further clouding the picture is the Green Drop report’s introduction of the contender awards. These are given to wastewater treatment works which fulfill all criteria but are disqualified from receiving a 90% score (the minimum for a certification award) because they fail to treat the effluent to minimum standards.

Contender status was awarded to 30 wastewater treatment works in the country, giving the impression their environmental impact is acceptable. However, eight of them failed dismally when it came to effluent quality, cumulatively releasing billions of liters of partially treated sewage into their catchments.

Releasing approximately one million liters of effluent into the Diep River daily, Potsdam wastewater treatment works was given an 89% score in the Green Drop report, yet it only met minimum standards for effluent quality 9% of the time during the year under review.

One of only six large estuaries on South Africa’s west coast, the Diep River estuary in Milnerton, Cape Town, experienced a major fish die-off in March. Estuaries such as these are critically important as fish nurseries, says marine biologist and founder and director of Anchor Environmental Consultants Dr. Barry Clark.

They are breeding grounds for a large number of species which are important for inshore fisheries – a critical source of livelihood for small-scale commercial and subsistence fishers, as well as recreational fishers who contribute to local economies.

“On the west coast, there are only five or six reasonably large estuaries, and the Diep River is one of them,” said Clark, with their scarcity making them “disproportionately important to fisheries.”

With Potsdam wastewater treatment works releasing huge volumes of wastewater into the Diep River estuary, it is in an “extremely poor state of health at the moment.”

He said the quality of wastewater flowing into the estuary has “deteriorated severely” over the last decade. “Diep River estuary is hugely important, and it’s a tragedy it’s effectively lost to society,” said Clark.

The putrid state of the estuary, known locally as the Milnerton Lagoon, has also impacted residents, who regularly post notices of sewage flows on a Facebook group, and, as Hanse’s story illustrates, shut down opportunities for youngsters from poor and working-class families living in townships nearby.

Milnerton Canoe Club chairperson Richard Allen said his organization used to run the development program that Hanse and other youth from nearby townships attended. But, he says, he had to shut it down when the water became so polluted that they could not risk a child falling in.

Allen said they used to have about 20 kids in the program who were spending time outside of an environment beset with social ills and instead spending time in a healthy sports environment. After the program had to be shelved, he says, “a lot of them backslid and went the other way.”

Membership of the club is also dwindling due to frequent sewage spills, making training days an uncertainty. He said about 30% of the members had left, choosing to travel to other relatively cleaner water bodies. This meant people who used to earn money as coaches there were no longer able to do so.

Allen added that the water was toxic, and the constant stench meant people living near the water’s edge could no longer sell their houses.

“It’s a disaster, a catastrophe,” he said.

The city of Cape Town is making efforts to upgrade Potsdam wastewater treatment works and rehabilitate the Diep River estuary, but it is falling short of meeting a directive meted out by the provincial Environmental Management Inspectorate, a state office responsible for enforcing environmental legislation, in 2020.

Something is fishy

Another of Cape Town’s high-scoring contender wastewater treatment works is Athlone, which releases effluent into the Black River, a major river running through the central city area. Athlone wastewater treatment works scored just 15% on average for microbiological compliance across 2020 and 2021, according to DWS data. Its chemical compliance levels were at 54% for the period. However, it obtained an overall Green Drop score of 89%.

Flowing through an industrial area, it is also polluted by high levels of heavy metals, as University of the Cape Town master’s student Lucy Gilbert found in 2015.

Yet the Black River remains a source of food and income for some Capetonians.

Abibat Lamidi runs a restaurant in the Maitland semi-industrial area near the Black River. She says she buys catfish caught in the Black River by informal fishers, paying between R30 ($1.76) to R50 ($2.93) a fish. Lamidi uses it as a base for a traditional pepper soup sought by her Nigerian customers.

But she says the taste of the Black River catfish is very different from catfish in Nigeria. “This catfish smells like petrol.” Lamidi disguises the taste with the strong spices that make up the dish.

Given studies revealing bioaccumulation of chemical compounds up the food chain in the diluted seawaters along Cape Town’s coast, the long-term effect of consuming fish from the Black River, where pollutants are more concentrated, is of concern.

Dumping of wastewater into rivers and oceans isn’t just bad for the environment and the marine life. As Petrik points out, it harms humans too.

“The compounds contained in some of these dumped products cause feminization and lower the quality of sperm. They can also lead to sexual abnormalities and reproductive impairments in both sea life and humans, as well as caus[e] persistent antibiotic resistance and endocrine disruption,” states Petrik.

As more research emerges on the deleterious effects of using these polluted bodies of water, locals and tourists are left wondering if they’ll ever be able to enjoy South Africa’s beaches again.

As Griggs concluded in her note to the City of Cape Town, “Unless the Cape Town authorities can do something about this problem, we fear that not only will you despoil this beautiful coast, but you will also lose tourists who will be as disgusted with the state of the beaches as we sadly are.”

By Steve Kretzmann

Data visualizations by Yuxi Wang

This investigation was produced in collaboration with the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism and OpenUp, with the support of the Open Society Foundation.

A version of this article was first published by GroundUp.

Published with permission.